This article was published on Arbona Health Hub Volume 1 Issue 1 (ISSN: 3065-5544).

Introduction

During my studies in medical school regarding the Development of the Male Genital Systems, a topic of discussion were some variants on the penis development. Hypospadias (HP) were one of the clinical correlations that were discussed, with an emphasis on the high prevalence on congenital variants in the population of Puerto Rico which affects around 1 to 125 live male births.This is second to Ventral Septal Defects, a type of heart defect, on the most prevalent findings. HP are defined as failure in closure of the ventral foreskin of the penis that can extend all the way to the scrotum. This will result in a variable location of the external urethral orifice, depending on where the failed closure occurred.

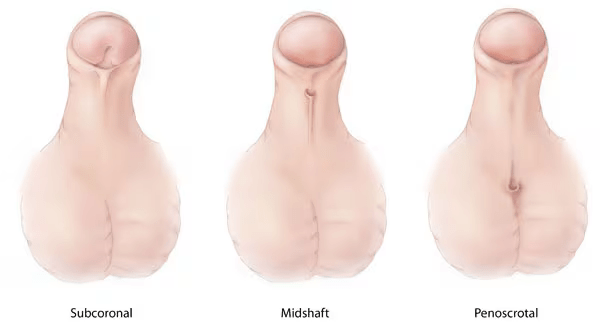

HP can be further classified on its severity regarding its anatomical location. This includes in the glandular penis or anterior (mild), midshaft/distal penis (moderate), or from proximal penis to perineal region (severe). It is believed that the underlying cause for HP are both genetical and environmental factors affect this development. Specifically, exposure to either estrogen or androgen like compounds in utero. Interestingly, males with HP have been associated to testicular, bladder, and prostate cancer, but also with male infertility (Lo E, et al 2020).

Findings

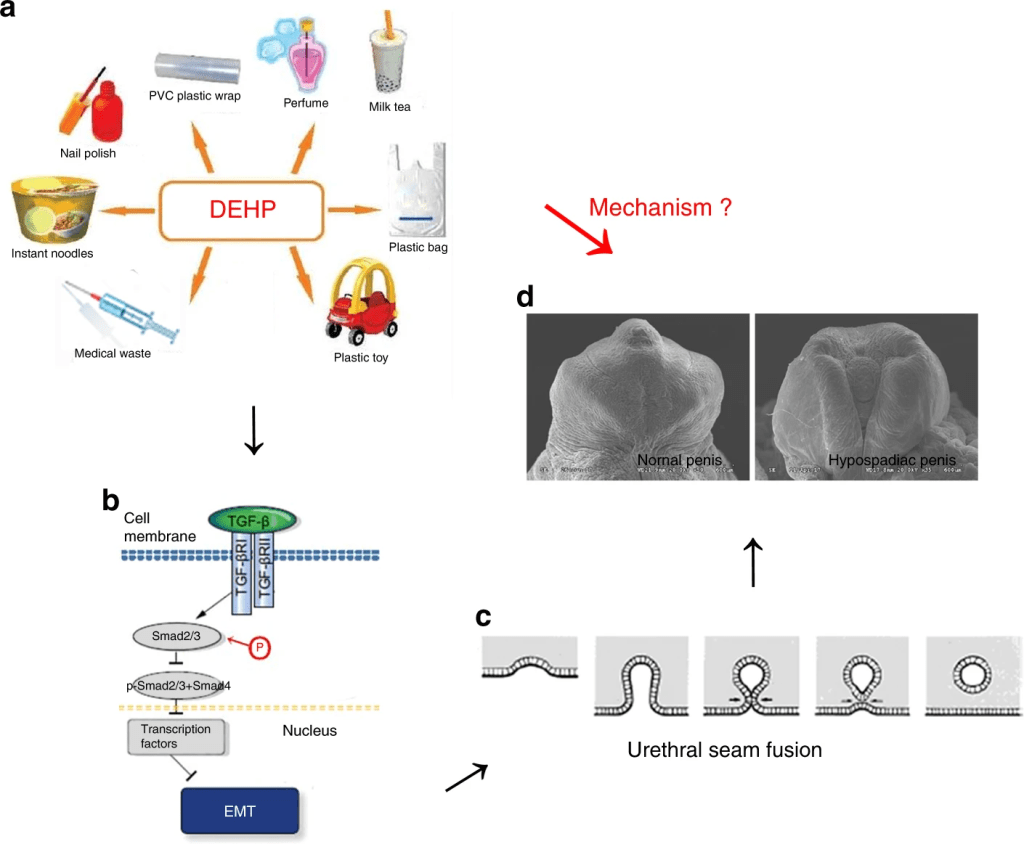

A main endocrinological disruptor that increases the likelihood for developing HP is Diethylhexyl phthalate (DHEP) a common plasticizer used in polyvinylchloride (PVC) plastics. The main mechanism for DEHP is decreasing the levels of Transforming Growth Factor β (TGF-β). It is important to note that this transcription factor is involved in molecular signaling pathways, that in the formation of male genitalia is epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). This mechanism is highly repeated in other process of embryology and some cancers, but it is generally a process where epithelial cells change to mesenchymal cells to give rise to other tissues and structures.

In the male penis, it has been characterized that urethral epithelial cells undergo EMT and fuse with urethral folds to form a urethral fusion plate. Eventually both sides are expected to fuse medially, giving the penis’ cylindrical shape. If the urethral seam gets halted, that is where hypospadias will develop. It has also been characterized that TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway regulates EMT in this region. When mice were exposed to DEHP this signaling pathway was inhibited, evidenced by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) with a defect in penis development. Specifically in ventral urethral groove, where failed closure was observed. Interestingly in light microscopy preparation, the urethral opening was observed towards the outside, where normally it would close towards the inside.

EMT markers such as E-cadherin and β-Catenin, among other proteins (which are epithelial biomarkers for EMT), confirmed by qRT-PCR, Western Blot and immunofluorescence, showed that failure to induce EMT will result in the formation of HP. A possible therapeutic to induce EMT despite DEHP is TGF-β1, where higher levels of this ligand will stimulate the EMT and prevent the formation of HP, as evidenced in this study (Zhou, Y, et al, 2020).

Another aspect to consider is the role of microRNA’s, which are small non-coding RNA molecules that regulate gene expression, that play part in the development of HP. microRNA-200c (miR-200), has specific action on regulating Zeb1 gene, which further regulates expression E-cadherin and vimentin, which are markers for EMT. Also, miR-200 has been found that it can reduce the effects of TGF-β1’s effects on inducing EMT. The specific mechanism is that miR-200 inserts in the 3’ Untranslated Region (3’UTR) of Zeb1’s messenger RNA, preventing its translation, and thus preventing the EMT. Meaning that when miR-200 is reduced and Zeb1 expression is increased, it will most likely result in the development of HP. So, a possible therapeutic is suggesting induction of miR-200 to further induce EMT and stimulating closure of ventral urethral groove. These findings lead the role on the pathogenesis of hypospadias (Quian, C. et al, 2016).

Another morphogen to consider in the development of HP is sonic hedgehog (SHH). Where aberrant expression of SHH can lead to failure of the formation of the genital tubercule. This in part cannot produce the phallus and persistent cloaca, which are structures related to the genitourinary system. Interestingly, transcription factors such as FOXA1 and FOXA2 regulate the transcription of SHH. However, only retaining a single copy of FOXA1 but mutation/deletion of FOXA2 retains division of the cloaca but will not form the urethral tube formation leading to the formation of HP. Leading to state that both genes are required to induce SHH to further induce the formation of the urethral tube and preventing the variant of HP. (Gredler, M. et al, 2020).

Conclusion

The development of hypospadias can be explained by different molecular signaling pathways. However, the common denominators in the pathways include EMT and proper formation of the urethral tube. Interestingly, distinct environmental hazards play a role in the development of hypospadias.

References

Gredler, M. L., Patterson, S. E., Seifert, A. W., & Cohn, M. J. (2020). Foxa1 and Foxa2 orchestrate development of the urethral tube and division of the embryonic cloaca through an autoregulatory loop with Shh. Developmental Biology, 465(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2020.06.009

Lo, E. M., Hotaling, J. M., & Pastuszak, A. W. (2020). Urologic conditions associated with malignancy. Urologic Oncology, 38(1), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2018.12.018

Qian, C., Dang, X., Wang, X., Xu, W., Pang, G., Chen, Y., & Liu, C. (2016). Molecular mechanism of MicroRNA-200c regulating transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)/SMAD family member 3 (SMAD3) pathway by targeting zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1) in hypospadias in rats. Medical Science Monitor: International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research, 22, 4073–4081. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.896958

Zhou Y, Huang F, Liu Y, Li D, Zhou Y, Shen L, Long C, Liu X, Wei G. TGF-β1 relieves epithelial-mesenchymal transition reduction in hypospadias induced by DEHP in rats. Pediatr Res. 2020 Mar;87(4):639-646. doi: 10.1038/s41390-019-0622-2. Epub 2019 Nov 14. PMID: 31726466.

[…] Guevárez Galán presents an in-depth look into the molecular mechanisms behind hypospadias (p. […]

LikeLike