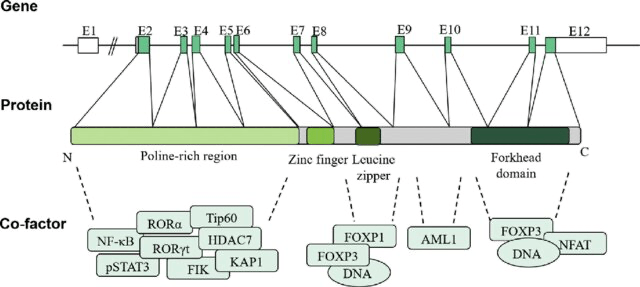

The immune system plays a crucial role in defending the body against pathogens through the coordinated action of specific immune cells, such as CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Among these, CD4+ T regulatory (Treg) cells serve a unique function: they suppress immune responses and prevent the immune system from mistakenly attacking the body’s own tissues. Treg cells must express the forkhead box P3 (FOXP3) gene—located on the X chromosome—to properly maintain immune homeostasis (Figure 1). FOXP3 is also involved in tissue repair and metabolic regulation (Savage et al., 2020).

Figure 1. Diagram of the FOXP3 gene structure, mRNA structure, and functional features. FOXP3 protein contains four distinct domains, including the N-terminal proline-rich region, central zinc finger, leucine zipper, and forkhead (FKH) domain. These domains can interact with different proteins to regulate transcriptional activity and affect Treg cell function. Reprinted from Huang Q, Liu X, Zhang Y, Huang J, Li D, Li B. Molecular feature and therapeutic perspectives of immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome. J Genet Genomics. 2020 Jan 20;47(1):17-26. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2019.11.011. Epub 2020 Jan 24. PMID: 32081609.

Treg Cell Differentiation and Function

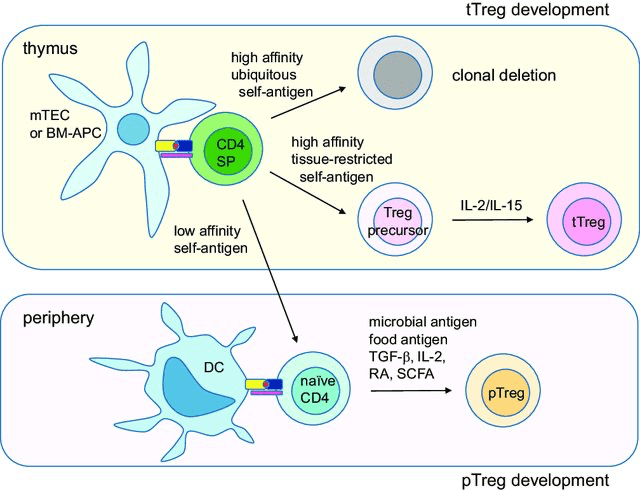

Although mutations in this gene can vary and cause different presentations, one of the most well-studied disorders associated with FOXP3 mutations is immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked (IPEX) syndrome. This rare X-linked recessive disorder typically presents during infancy and leads to systemic autoimmunity due to the failure of Treg cell development or function. IPEX syndrome is characterized by polyendocrine dysfunction, chronic enteropathy, and dermatitis (Ben-Skowronek, 2021). Natural Tregs are produced in the thymus during T cell development, while induced Tregs can be generated in peripheral tissues—both of which are essential for maintaining immune tolerance and preventing autoimmunity (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of Treg cell development. tTreg cells develop in the thymus by two-step process. First, high-affinity tissuerestricted self-antigens presented by medullary thymic epithelial cells (mTECs) or bone-marrow derived antigen-presenting cells (BM-APCs) derive single-positive (SP) T cells into Treg pathway. Second, cytokine IL-2 or IL-15 derives the precursor cells into fully committed tTreg cells. pTreg cells develop in the periphery by environmental antigens such as microbial antigens or food antigens presented by mucosal tissue-resident dendritic cells (DCs). TGF-β, retinoic acids (RAs) and short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) produced in the immunosuppressive environments promote pTreg development. Reprinted from Lee W, Lee GR. Transcriptional regulation and development of regulatory T cells. Exp Mol Med. 2018 Mar 9;50(3):e456. doi: 10.1038/emm.2017.313. PMID: 29520112; PMCID: PMC5898904.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

IPEX Syndrome commonly manifests with three hallmark clinical features—enteropathy, endocrinopathy, and dermatitis—all of which begin in the first year of life (Ben-Skowronek, 2021). Enteropathy presents as intractable diarrhea and is unresponsive to dietary interventions due to immune-mediated damage to the intestines (Gentile et al., 2012). Endocrinopathy most often takes the form of early-onset type 1 diabetes, sometimes emerging within the first weeks of life (Husebye et al., 2018). Dermatologic manifestations include atopic or psoriasiform dermatitis, though more rare presentations such as autoimmune, allergic, or infectious skin conditions have also been reported (Barzaghi & Passerini, 2021). Additional complications may include nephropathy, hepatitis, thyroid disease, and bone marrow abnormalities. Diagnosis is confirmed via genetic testing for pathogenic FOXP3 variants (Tan et al., 2004). The syndrome is extremely rare, with an estimated prevalence of fewer than 1 in 1,000,000 individuals (Tan et al., 2004).

Management and Treatment

The management of IPEX Syndrome centers around immunosuppressive therapy to mitigate the autoimmune response. This is supplemented by symptom-specific interventions such as supplemental nutrition for enteropathy, topical treatments for dermatitis, insulin therapy for diabetes, and thyroid hormone replacement when needed (Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, 2022). For patients who are eligible, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) offers the potential for long-term remission. HSCT is more effective in patients with less organ involvement, but it is constrained by donor availability and its high risk-benefit ratio (Barzaghi et al., 2018). Rapamycin has emerged as a preferred agent for immunosuppressive therapy and is particularly notable for its ability to modulate Treg cell function through FOXP3-independent pathways (Passerini et al., 2020). These mechanisms provide new insights into disease control and suggest further directions for treatment innovation.

In severe cases, patients often die within the first two years of life. However, immunosuppressive therapy has allowed for stabilization in many patients until HSCT can be performed (Immune Deficiency Foundation, n.d.). Future research should prioritize understanding the molecular heterogeneity of FOXP3 mutations and their functional impact, which could improve prognostic assessments and inform personalized treatment strategies.

Conclusion

Immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked (IPEX) syndrome is a rare genetic disorder caused by mutations in the FOXP3 gene, which disrupts Treg cell development and function, ultimately leading to widespread autoimmunity. The syndrome typically presents with enteropathy, endocrinopathy, and dermatitis. While immunosuppressive therapy and HSCT offer effective interventions, each comes with significant limitations. Rapamycin shows promise as a FOXP3-independent modulator of immune suppression. Continued research into the mechanisms of Treg cell regulation, FOXP3 mutation profiling, and novel therapeutic options is essential for improving outcomes in IPEX patients. Future efforts should also focus on earlier diagnosis, donor expansion for HSCT, and targeted gene therapies.

References

Cover Image: FOXP3 by Ismaïl Jarmouni, retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=86104165. Used under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Figure 1. Reprinted from Huang Q, Liu X, Zhang Y, Huang J, Li D, Li B. Molecular feature and therapeutic perspectives of immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome. J Genet Genomics. 2020 Jan 20;47(1):17-26. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2019.11.011. Epub 2020 Jan 24. PMID: 32081609.

Figure 2. Reprinted from Lee W, Lee GR. Transcriptional regulation and development of regulatory T cells. Exp Mol Med. 2018 Mar 9;50(3):e456. doi: 10.1038/emm.2017.313. PMID: 29520112; PMCID: PMC5898904.

- Savage, P. A., Klawon, D. E. J., & Miller, C. H. (2020). Regulatory T Cell Development. Annual Review of Immunology, 38, 421–453. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-immunol-100219-020937

- Huang, Q., Liu, X., Zhang, Y., Huang, J., Li, D., & Li, B. (2020). Molecular feature and therapeutic perspectives of immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome. Journal of Genetics and Genomics, 47(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgg.2019.11.011

- Ben-Skowronek, I. (2021). IPEX Syndrome: Genetics and Treatment Options. Genes, 12(3), 323. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12030323

- Lee, W., & Lee, G. R. (2018). Transcriptional regulation and development of regulatory T cells. Experimental & Molecular Medicine, 50(3), e456. https://doi.org/10.1038/emm.2017.313

- Gentile, N. M., Murray, J. A., & Pardi, D. S. (2012). Autoimmune enteropathy: a review and update of clinical management. Current Gastroenterology Reports, 14(5), 380–385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11894-012-0276-2

- Husebye, E. S., Anderson, M. S., & Kämpe, O. (2018). Autoimmune Polyendocrine Syndromes. The New England Journal of Medicine, 378(12), 1132–1141. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1713301

- Barzaghi, F., & Passerini, L. (2021). IPEX Syndrome: Improved Knowledge of Immune Pathogenesis Empowers Diagnosis. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 9, 612760. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.612760

- Tan, Q. K. G., Louie, R. J., & Sleasman, J. W. (2004). IPEX Syndrome. In Adam, M. P., Feldman, J., Mirzaa, G. M., et al. (Eds.), GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2023. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1118/

- Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. (2022). IPEX syndrome. Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.https://www.chop.edu/conditions-diseases/ipex-syndrome

- Barzaghi, F., Amaya Hernandez, L. C., Neven, B., et al. (2018). Long-term follow-up of IPEX syndrome patients after different therapeutic strategies: An international multicenter retrospective study. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 141(3), 1036–1049.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2017.10.041

- Passerini, L., Barzaghi, F., Curto, R., et al. (2020). Treatment with rapamycin can restore regulatory T-cell function in IPEX patients. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 145(4), 1262–1271.e13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2019.11.043

- Immune Deficiency Foundation. (n.d.). IPEX syndrome. https://primaryimmune.org/understanding-primary-immunodeficiency/types-of-pi/ipex-syndrome