This article was published on Arbona Health Hub Volume 2 Issue 1 (ISSN: 3065-5544).

In the early 20th century, Puerto Rico (PR) had recently been acquired by the United States of America (USA) as part of the Treaty of Paris after the Spanish-Cuban-American War of 1898. Puerto Ricans faced new opportunities and challenges as they navigated life under the new governing power of the USA. They began to adjust to new laws, systems, and cultural influences.

For Puerto Ricans aspiring to work in the medical industry, the lack of local medical schools meant traveling abroad to pursue an education. However, for Puerto Rican women, this path was exponentially difficult. In addition to financial and logistical challenges, they faced societal expectations and systematic barriers that discouraged women from entering the workforce, specifically male-dominated fields such as medicine. Despite these barriers, a small but determined group of Puerto Rican women paved the way for future generations of female physicians.

Puerto Rican Academy of the Women’s Medical College of Baltimore

Most medical colleges in the United States of America opposed admitting women into their programs during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This problem led to the creation of the Women’s Medical College of Baltimore was founded in 1882 (Emerson Lantz, 1918). This groundbreaking institution was designed to provide women with access to medical education by offering a space specifically for women. The college became a vital stepping stone for women pursuing careers in medicine, producing many skilled female physicians.

The Women’s Medical College of Baltimore opened its doors to Puerto Ricans after the implementation of the Puerto Rican Academy by a fellow islander, Dr. Rafael Janer (Barceló Miller, 1992). He established this academy to serve as an academic center for which Puerto Ricans began migrating. Elisa Rivera and Anita Janer were the first Puerto Rican women to graduate from this institution (Emerson Lantz, 1918; Azize Vargas & Avilés, 1990; La Correspondencia de Puerto Rico, 1906). Nevertheless, their time at this academy was not without challenges. They were forbidden to speak Spanish and were forced to follow strict rules (The Baltimore Sun, 1908). Despite these hardships, they and many other Puerto Rican women that followed set the stage for the future generations of Puerto Rican female physicians.

Social and Medical Impact of the First Female Physicians in Puerto Rico

The contributions of Puerto Rico’s first female physicians extend far beyond medicine. Many of these female pioneers became influential figures in the fight for women’s rights and social justice. Dr. Dolores “Lola” Pérez Marchand, for example, dedicated her life to women and children’s health, practicing for many years at the Women’s Hospital in Ponce. Beyond her work in medicine, she played a significant role in Puerto Rico’s feminist movement, joining the Commission of the Association of Puerto Rican Suffragist Women. Through her advocacy, Dr. Pérez Marchand fought in Washington, DC for the Puerto Rican women’s right to vote (Azize Vargas & Avilés, 1990; Negrón Muñoz, 1935).

Dr. Palmira Gatell, who graduated from the Women’s Medical College in 1910 (Barceló Miller, 1992; Azize Vargas & Avilés, 1990), became the first woman to participate in a meeting of the Medical Association, a space overwhelmingly dominated by men. This bold decision was not easy, considering the widespread opposition to female representation during the suffrage movement. She also served as President of the Women’s Civic Club and the Board Pro Children’s Hospital, fighting for women and children’s access to healthcare (Azize Vargas & Avilés, 1990).

Dr. Martha (María) Robert de Romeu became the first Puerto Rican female physician to graduate from a co-educational medical college. She earned her degree at Tufts Medical College in Boston, one of the first institutions to admit both men and women without requiring separate programs for female students (Azize Vargas & Avilés, 1990). After returning to PR, Dr. Robert dedicated her career to advancing women’s health. She practiced in the San Aurelio Hospital and the Department of Gynecology of the Polyclinic in Mayagüez. Like many pioneering women of her time, Dr. Robert also participated in many social and political movements such as the Suffragist Social League and the Women National Party (Azize Vargas & Avilés, 1990; Negrón Muñoz, 1935).

During these conflicting times, it was rare for women to participate in top positions of healthcare or politics. Nevertheless, these Puerto Rican figures changed this course of history. Dr. Robert was the first woman appointed as Director of the Maternal and Child Hygiene Bureau within Puerto Rico’s Department of Health, providing solutions for maternal and infant mortality (Azize Vargas & Avilés, 1990). During this role, the Department of Health saw a significant decline in maternal-infant mortality rates, reinforcing the role that women can play in shaping healthcare policies, especially in matters of women’s health (Azize Vargas & Avilés, 1990).

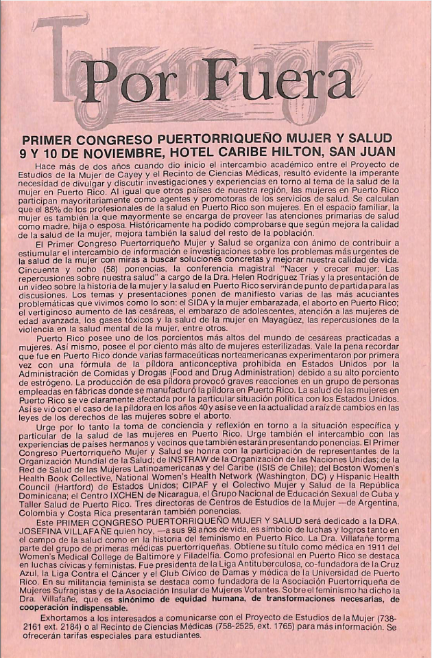

Dr. Josefina Villafañe, after completing her medical studies on the mainland (Barceló Miller, 1992), became a key figure in Puerto Rico’s fight against tuberculosis. She held a significant position as the President of the Anti-tuberculosis League in PR, bringing services and medical advances for the Puerto Rican community during this epidemic (Azize Vargas & Avilés, 1990). Also a passionate advocate for women’s rights, Dr. Villafañe strongly supported the feminist movement. She believed feminism was a path to include female intelligence and female art throughout the world, searching for equity and justice for women (Negrón Muñoz, 1935). In recognition of her incredible legacy, the medical community in Puerto Rico dedicated the first Puerto Rican Congress on Women and Health to Dr. Villafañe in 1989, honoring her contributions to women, female physicians, and the medical community (Proyecto de Estudios de la Mujer del Colegio Universitario de Cayey, 1989).

With the onset of World War I, women like Dr. Dolores Mercedes Piñero sought to contribute to the war effort by joining the United States Military, hoping to serve in environments that needed female representation. As one of the first Puerto Rican female physicians (Azize Vargas & Avilés, 1990), Dr. Piñero was well aware of the challenges she would face, especially considering that Puerto Rico had only recently been granted U.S. citizenship. After initially being rejected by the U.S. military due to her gender, Dr. Piñero did not give up. She persisted and was eventually assigned to the Medical Service Corps of the Army Medical Department, a milestone for women across the country (Jensen, 1993; Serrano, 2020).

Reflecting on the Legacy

The journey of Puerto Rican female physicians during the early 20th century represents an inspiring story of resilience, determination, and progress for the Puerto Rican community. These pioneers not only overcame systemic barriers to education and professional development, but also became advocates for social and political change. Through their dedication to women and children’s health, advocacy for women’s rights, and tireless work in medicine, they shattered societal norms and created a legacy.

The impact of their legacy continues to pave the way for medical students today, teaching us the importance of the commitment we make to our island of Puerto Rico. Additionally, they remind us of the importance of fostering diversity and inclusion in the medical profession.

As we reflect on their lives, we honor their courage to break barriers and bring the female perspective into the world of medicine. May their stories continue to inspire future generations of women in medicine, carrying forward their legacy.

References

Emerson Lantz, E. (1918, May 13). The Women’s Medical College of Baltimore. Evening Sun.

Barceló Miller, M. d. F. (1992). Estrenando togas: la profesionalización de la mujer en Puerto Rico, 1900-1930. Revista del Instituto de Cultura Puertorriqueña, (99), 58-70. La Colección Puertorriqueña. https://issuu.com/coleccionpuertorriquena/docs/primera_serie_n__mero_99/61

Azize Vargas, Y., & Avilés, L. A. (1990). Los Hechos Desconocidos: participación de la Mujer en las Profesiones de Salud en Puerto Rico (1898-1930). Puerto Rico Health Sciences Journal, 9(1). PRHSJ. https://md.rcm.upr.edu/download/los-hechos-desconocidos-la-mujer-en-las-profesiones-de-salud-en-puerto-rico-1898-1930/

La Correspondencia de Puerto Rico. (1906, June 25). Las primeras doctoras puertorriqueñas. La Correspondencia de Puerto Rico, 1.

The Baltimore Sun. (1908, October 25). This Modest Baltimore School is Training the Future Rulers of Porto Rico. The Baltimore Sun, 17.

Negrón Muñoz, A. (1935). Mujeres de Puerto Rico: Desde el periodo de colonización hasta el primer tercio del siglo XX. Imprenta Venezuela. https://issuu.com/coleccionpuertorriquena/docs/mujeres_pr_negron_munoz

Proyecto de Estudios de la Mujer del Colegio Universitario de Cayey. (1989, September). Boletín Oficial del Proyecto de Estudios de la Mujer del Colegio Universitario de Cayey [Primer Congreso Puertorriqueño Mujer y Salud]. In Tejemenje (2nd ed., Issue 4). Cayey, Puerto Rico. https://www.upr.edu/cayey/wp-content/uploads/sites/10/2021/05/tejemeneje-agosto-noviembre-1989.pdf

Jensen, K. (1993). Uncle Sam’s Loyal Nieces: American Medical Women, Citizenship, and War Service in World War I. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 67(4), 670-690. JSTOR. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44445837

Serrano, A. (2020, June 19). Dolores Mercedes Piñero. Women Activism NYC. https://www.womensactivism.nyc/stories/4286