This article was published on Arbona Health Hub Volume 1 Issue 2 (ISSN: 3065-5544).

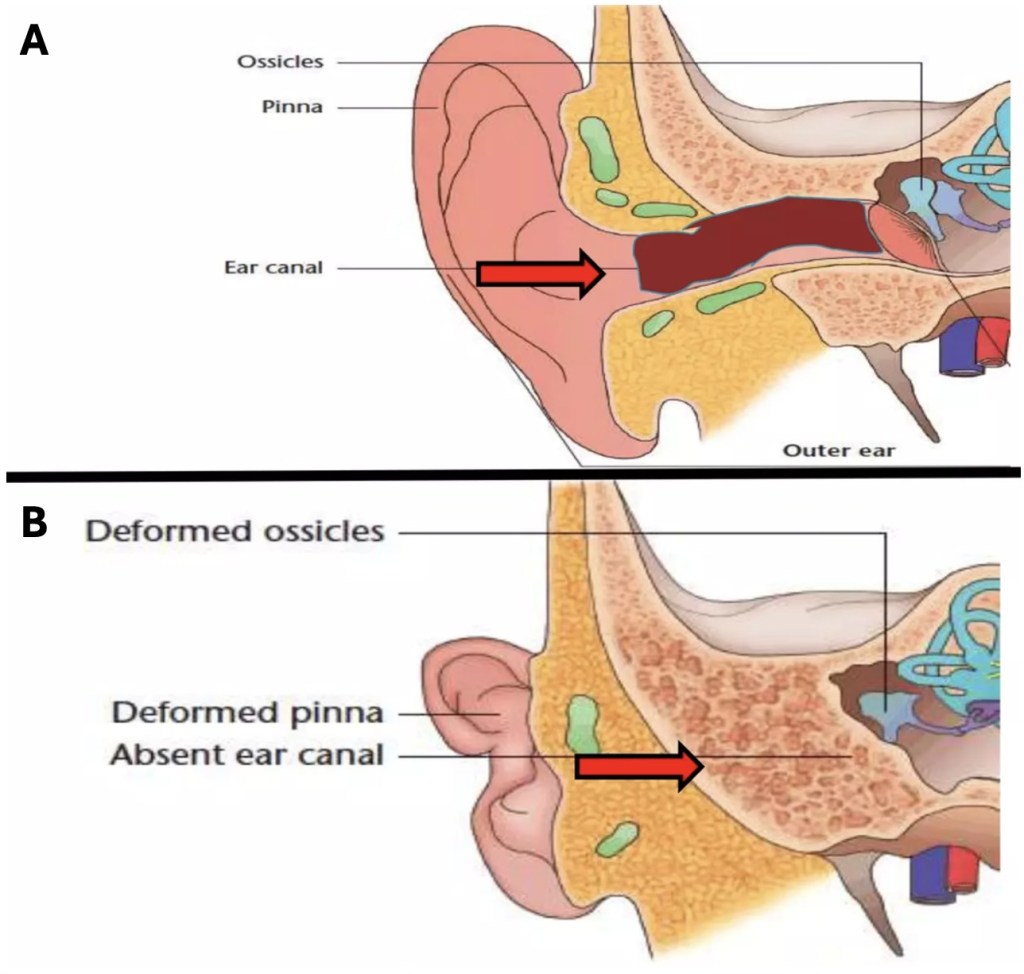

The external acoustic meatus, also known as the external auditory canal, is a structure found in the external part of the ear that serves to connect the outside world to the middle ear and acts as a passageway for sound waves heading towards the tympanic membrane. Due to the presence of this canal, and the funneling action of the auricle, sound waves are able to initiate the vibratory mechanism of sound conduction.

Atresia (Greek for ‘absence of an opening’) of this canal can lead to a partial or total loss of hearing capability. Congenital aural atresia is a condition characterized by the atresia, or narrowing, of the external auditory canal and often presents with various associated ear anomalies, such as microtia (Greek for ‘micro’ and ‘otia’, meaning ‘little ear’) and malformations affecting the middle and inner ears (Abdel – Aziz, 2013). It is imperative to diagnose and promptly treat newborns with this condition to ensure adequate language development (Lim et al., 2023). Treatment options for congenital aural atresia vary and include the implementation of bone-anchored hearing aids and the surgical creation of an ear canal, a procedure known as atresiaplasty (Pellinen et al., 2018).

Bone-Anchored Hearing Aids (BAHA)

Classical air–conducting hearing aids are inadequate for use in this condition, because they rely on the existence of a canal in order to amplify sound waves, which is why bone–conducting hearing aids are preferred. Bone–anchored hearing aids (BAHA) are a special type of bone–conducting hearing aids that are commonly used in patients living with conductive hearing loss, such as those with congenital auricular atresia (Hagr, 2007). These bone–anchored hearing aids consist of a titanium screw, implanted directly into the skull, that holds a bone–conducting hearing aid; vibrations are carried by the screw to the skull and vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII), allowing the transmission of auditory information (Farnoosh et al., 2014). You can view a video explaining how these devices work here.

BAHA have several advantages over other bone–conducting aids, which are not permanently attached to the skull. For example, they tend to be more comfortable and provide higher sound quality, since the structures that overlay the skull, such as the skin, do not interfere with the vibrations (Hagr, 2007). As with all procedures, complications related to BAHA implantations exist, including infections and the inadequate integration of the device into the bone (Farnoosh et al. 2014).

Atresiaplasty

Atresiaplasty is another common way to remedy congenital aural atresia. According to Li et al. (2014), atresiaplasty is a surgical technique that involves the creation of a cavity reaching the area of the tympanic membrane, so that an artificial external ear canal may be created. Skin grafts are then inserted into the ear, in order to cover the newly–made canal (Abdel – Aziz, 2013). As mentioned previously, congenital aural atresia may involve a variety of malformations to other parts of the ear, which is why this correctional surgery is oftentimes coupled with other procedures, such as ossicular replacements and tympanic membrane reconstruction (Li, 2014).

Complications of Atresiaplasty

Several complications related to the atresiaplasty surgery are known and may negatively affect the patient’s hearing. Closure of the artificial canal, infections due to problematic skin grafts, and lateralization of the tympanic membrane, which causes it to separate from the ossicles, are possible complications of this procedure (Abdel–Aziz, 2013). Due to its proximity to the surgical area, the facial nerve (CN VII) may be damaged, resulting in partial or complete unilateral facial paralysis, which is why extreme care must be taken during this procedure (Abdel–Aziz, 2013). Even in the absence of these complications, the procedure may not completely or adequately restore hearing, necessitating the continued use of hearing aids (Farnoosh et al., 2014).

Comparing BAHA and Atresiaplasty Outcomes

The use of BAHAs and the atresiaplasty technique are common treatments for congenital aural atresia, and several studies have attempted to compare the effectiveness of these remedies. According to Farnoosh et al. (2014), people who underwent atresiaplasties had “poorer audiological outcomes when compared to the BAHA group,” and experienced “a mild deterioration over time in hearing gain.” These conclusions are based on data that found that the BAHA group had a 44.3 ± 14.3 dB hearing gain in the short-term and a 44.5 ± 11.3 dB hearing gain in the long-term, while the atresiaplasty group experienced a gain of 20.0 ± 18.9 dB in the short-term and 15.3 ± 19.9 dB in the long-term (Farnoosh et al., 2014).

Another study states that patients in the BAHA group experienced a postoperative hearing gain of 46.9 ± 7.0 dB at 6 months and 39.8 ± 7.2 dB at 1 year, compared to the atresiaplasty group, which led them to conclude that atresiaplasty is as efficient as BAHA only when used in conjunction with hearing aids (Bouhabel et al., 2011). However, Bouhabel et al. did not provide explicit hearing gain data for atresiaplasty without hearing aids. Their conclusion hinges on the complementary use of hearing aids with atresiaplasty, which may explain the discrepancy with Farnoosh et al.’s findings. Despite atresiaplasty seemingly correcting the underlying defect, several studies have suggested that BAHAs tend to offer better and more consistent outcomes overall.

Conclusion

Congenital aural atresia results in the total or partial loss of the external auditory canal and, therefore, can lead to varying degrees of auditory problems in affected patients. Bone–anchored hearing aids allow the direct transmission of vibratory information and provide high sound quality, while surgical atresiaplasty creates an artificial canal in order to substitute the incomplete or absent external auditory meatus. BAHAs tend to be safer and provide more complete hearing outcomes, compared to surgical atresiaplasty.

References

Figure 1 image credit: https://microtiaatresia.com.au/hearing-loss/

Abdel – Aziz, M. (2013). Congenital Aural Atresia. The Journal of Craniofacial Surgery, 24(4), e418 – e422. 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182942d11

Lim. R., Abdullah, A., Hashmin, W. F. H., & Goh, B. S. (2023). Hearing rehabilitation in patients with congenital aural atresia: an observational study in a tertiary center. The Egyptian Journal of Otolaryngology, 39(90).https://doi.org/10.1186/s43163-023-00436-w

Pellinen, J., Vasama, J. P., & Kivekas, I. (2018). Long – term results of atresiaplasty in patients with congenital aural atresia. Acta Oto – Laryngologica, 138(7), 521 – 624. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00016489.2018.1431402

Hagr, A. (2007). BAHA: Bone – Anchored Hearing Aid. International Journal of Health Sciences, 1(2), 265 – 276. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3068630/#:~:text=The%20BAHA%20system%20uses%20an,the%20skin%20and%20subcutaneous%20tissues

Farnoosh, S., Mitsinikos, F. T., Maceri, D., & Don, D. M. (2014). Bone – Anchored Hearing Aid vs. Reconstruction of the External Auditory Canal in Children and Adolescents with Congenital Aural Atresia: A Comparison Study of Outcomes. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 2(5). https://doi.org/10.3389%2Ffped.2014.00005

Li, C., Zhang, T., Fu, Y., Qing, F., & Lu, F. (2014). Congenital aural atresia and stenosis: Surgery and long – term results. International Journal of Audiology, 53, 476 – 481. 10.3109/14992027.2014.890295

Bouhabel, S., Arcand, P., & Saliba, I. (2012). Congenital aural atresia: Bone – anchored hearing aid vs. external auditory canal reconstruction. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 76(2), 272 – 277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.11.020