This article was published on Arbona Health Hub Volume 1 Issue 2 (ISSN: 3065-5544).

Hello! Welcome back to the AGEs series. This is the third entry for this series, where we focus on understanding what are Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs) and discuss novel research findings on this topic. If you have missed our past two entries or would like to refresh your memory on the topic, I suggest you go back and read these articles, which I will link here (Entry 1) (Entry 2).

Aim and conclusion from the main article of reference

During my most recent literature search I came across a systematic review conducted by Chen et al. (2024) that aimed to clarify inconsistent findings regarding levels of the soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products (sRAGE) in both type 1 diabetes (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes (T2DM). The article concluded that sRAGE levels increased in T1DM patients and T2DM patients with complications, while decrease in newly diagnosed T2DM patients. Results indicated that changes in sRAGE levels in patients with T1DM or T2DM depend on the different types and stages of the disease. I believe you will make better sense of this information after you have read this entry.

This article was very insightful and went into detail to explain from a molecular level how diabetes and AGEs are related through some of the disease’s chronic complications. In this entry I will focus on explaining how AGEs are involved in one of the major mechanisms underlying the development and progression of complications associated with diabetes. Let’s dive in!

Diabetes and Its Complications

Diabetes is a chronic condition characterized by the body’s inability to properly regulate blood sugar levels, either due to insufficient insulin production (T1DM) or insulin resistance (T2DM). Complications from diabetes arise when high blood sugar levels persist over time, leading to damage in blood vessels and nerves. This can result in conditions such as heart disease, kidney failure, nerve damage, vision loss, and poor wound healing, significantly impacting overall health and quality of life (1) (2). It is known that AGEs and their associated molecular pathways play a role in exacerbating some of these complications in patients.

How AGEs Interact with RAGE

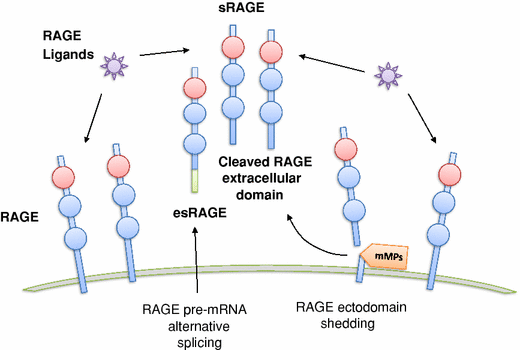

From our past entries in this series, you should remember that AGEs formation is accelerated in hyperglycemia, due to increased availability of glucose. Hence, in a patient with diabetes we should except to encounter a higher quantity of AGEs. AGEs can directly capture and crosslink proteins or bind to advanced glycation end product receptor (RAGE) and activate signaling pathways that lead to inflammation and oxidative stress (like we have discussed in the past). AGEs may bind to RAGE in different forms: full-length RAGE (fl-RAGE) and soluble RAGE (sRAGE). Here are the differences between them:

Full-Length RAGE (fl-RAGE):

- This is the membrane-bound form of the receptor.

- It is expressed on the surface of various cell types and plays a crucial role in mediating the effects of AGEs and other ligands.

- Activation of fl-RAGE triggers intracellular signaling pathways that can lead to inflammation, oxidative stress, and cellular dysfunction.

Soluble RAGE (sRAGE):

- This term generally refers to all soluble forms of RAGE that are released into the circulation.

- Soluble RAGE acts as a decoy receptor, binding to AGEs and preventing them from interacting with fl-RAGE, thereby potentially mitigating the harmful effects associated with AGEs.

- It includes both esRAGE and cRAGE.

Endogenous Secretory RAGE (esRAGE):

- esRAGE is a splice variant of RAGE that is secreted by cells.

- It is produced through alternative splicing of the RAGE gene and is found in the bloodstream.

- Like sRAGE, esRAGE can bind to AGEs and other ligands, helping to modulate their effects and reduce inflammation.

Cleaved RAGE (cRAGE):

- cRAGE is generated through the proteolytic cleavage of full-length RAGE by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs).

- This form is also soluble and can circulate in the blood.

- Similar to esRAGE, cRAGE can bind to AGEs, acting as a decoy receptor and potentially reducing the activation of fl-RAGE.

In summary, while full-length RAGE is the active receptor on cell membranes, soluble RAGE forms (esRAGE and cRAGE) are released into circulation and serve to modulate the effects of AGEs by preventing their interaction with fl-RAGE. sRAGE are recognized as protective receptors.

Complications and Genetic Factors

The meta-analysis provides clarity to inconsistent findings concerning sRAGE levels in T1DM and T2DM, showing that sRAGE levels are elevated in T1DM patients and in T2DM patients with complications, while a decrease is observed in newly diagnosed T2DM patients.

The increase in sRAGE levels is suggested to be a compensatory response to the chronic hyperglycemia, inflammation, and oxidative stress associated with diabetes. As advanced glycation end products (AGEs) accumulate, they exacerbate these conditions, leading to increased expression of RAGE and subsequent shedding of its extracellular domains, which contributes to higher sRAGE levels.

The Need for Tailored Diabetes Management

The authors also note that certain medications, such as insulin and oral hypoglycemic agents, can influence sRAGE levels. Clinical studies have shown that sRAGE levels can rise significantly after treatment with these medications, indicating that pharmacological interventions may play a role in modulating sRAGE. This suggests that managing diabetes through medication not only helps control blood glucose levels but may also impact sRAGE levels, potentially affecting the progression of diabetes-related complications.

If medications, such as insulin and oral hypoglycemic agents, lead to increased sRAGE levels, this could be a protective mechanism. Higher sRAGE levels may help mitigate the harmful effects of AGEs and reduce inflammation, potentially leading to better management of diabetes-related complications. In this scenario, effective medication management could help slow down or prevent the progression of complications, such as neuropathy, retinopathy, and cardiovascular issues.

Conversely, if the management of diabetes does not adequately control blood glucose levels or if it leads to decreased sRAGE levels, this could result in a more aggressive progression of complications. Lower sRAGE levels may be associated with increased inflammation and oxidative stress, which can exacerbate tissue damage and lead to a higher risk of complications. The relationship is complex and underscores the importance of tailored treatment strategies in diabetes care.

Furthermore, the discussion emphasizes that the presence of complications in T2DM patients is a significant factor affecting sRAGE levels. The authors suggest that damage to target organs may be linked to the observed elevations in sRAGE, highlighting the need for further research to understand these mechanisms. The article also mentions that genetic factors can significantly affect sRAGE levels and, consequently, the progression of diabetes-related complications. Understanding these genetic influences can help tailor treatment strategies to improve outcomes for individuals with diabetes.

Conclusion

The authors call for more experimental studies to elucidate the specific mechanisms behind the changes in sRAGE levels in diabetes, as well as the potential implications for treatment strategies aimed at managing AGEs and their effects on diabetic complications. Overall, the discussion underscores the complexity of the relationship between AGEs, sRAGE, and diabetes, emphasizing the importance of understanding these interactions for better management of the disease and its complications.

Thank you for taking the time to explore the connections between AGEs, sRAGE, and diabetes with me. I hope you found this discussion insightful and engaging. If you’re curious to learn more, I encourage you to dive deeper into the subject and share your thoughts, questions, or suggestions for future topics in the comments. Your feedback and ideas are always welcome!

References

Cover image was generated using AI. It is not meant to represent the actual appearance of the AGEs.

Figure 1. Vazzana, N., Santilli, F., Cuccurullo, C. et al. Soluble forms of RAGE in internal medicine. Intern Emerg Med 4, 389–401 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-009-0300-1

Figure 2. https://www.flickr.com/photos/sriram/2219886844

Chen, Q., Liu, L., Ke, W., Li, X., Xiao, H., & Li, Y. (2024). Association between the soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products and diabetes mellitus: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC endocrine disorders, 24(1), 232. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-024-01759-2

Vazzana, N., Santilli, F., Cuccurullo, C. et al. Soluble forms of RAGE in internal medicine. Intern Emerg Med 4, 389–401 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-009-0300-1