This article was published on Arbona Health Hub Volume 1 Issue 2 (ISSN: 3065-5544).

People often talk about cancer and the ruthless, painful, and terrifying disease it can be. With incidences in the USA of 440.5 per 100,000 men and women per year (National Institute of Cancer, 2017-2021). According to the World Health Organization, “in 2022, there were 20 million new cases and 9.7 million deaths from cancer worldwide,” making it one of the leading causes of death worldwide (World Health Organization, 2022).

Many wonder, even I did until almost halfway through my undergraduate degree, about what makes cancer so bad. Why does it end life as we know it? All these questions deserve an explanation that science attempts to offer. This article aims to describe, in a general and easy-to-understand manner, the different elements associated with death from cancer. I must clarify that this article does not intend to represent an exhaustive analysis of the cellular, molecular and biochemical mechanisms of death from cancer, but rather a general summary of the elements involved in the collapse of life and the development of cancer.

Introduction

First, it is important to define cancer. This disease is understood as an uncontrolled proliferation of cells caused by DNA damage of different genes involved in cell replication. Following multiple mutations, this initial localized irregular division of cells can transform into a mass (i.e. tumor) and extend to other organs. The arrival of these abnormal cells to fundamental parts of the human body, such as the brain, the lungs, among others, is the problem.

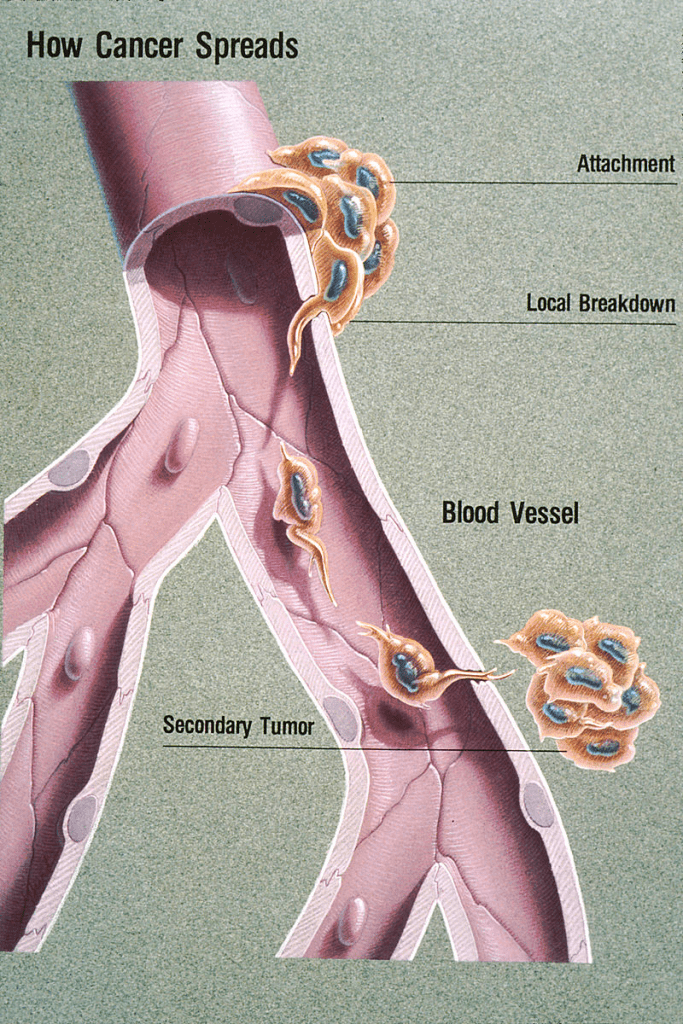

The masses that form can be benign or malignant. A benign tumor is a localized cancer that is non-migrating to other parts of the body. A malignant cancer can occur when abnormal cells reach the lymphatic or vascular vessels and travel to other parts of the body, continuing their uncontrolled proliferation. This is better known as metastases and is considered a more complicated health scenario since the cancer can virtually reach any part of the body, compromising essential structures and processes for human life.

Mechanism of Cancer Death

According to various sources, the mechanisms involved in death from cancer are complex and multifactorial. These include a series of structural and chemical changes that cause the deterioration of vital structures. In some cases, cancer can compress vascular structures causing tissue hypoxia, or in other words lack oxygen supply. It can also include the destruction of organ parenchyma causing serious cascades of inflammation and tissue damage, among many others. In other cases, cancer can cause severe external or internal bleeding due to tumor invasion of blood vessels. This hemorrhage can cause rapid blood loss, leading to a decrease in blood pressure and the development of hypovolemic shock. If not properly controlled, this can be life-threatening due to organ hypoxia.

Depending on the location and extent of the tumor, local complications may arise such as hormone imbalances, urinary, respiratory or intestinal tract obstruction, severe bleeding and others. These abnormalities can affect vital signs, such as blood pressure, heart rate, breathing, and body temperature, and eventually lead to multiple organ failure and death. According to Sonoda, as cancer progresses and invades tissues, there is an increasing risk of failure of major organs, including the liver, lungs, kidneys and heart, which could lead to organism collapse (Sonoda, 2016).

In addition to the natural effects of cancer itself, side effects of prescribed treatments, such as radiotherapy, chemotherapy or surgery, can also contribute to the weakening of the body and increase the risk of serious complications. For example, patients could be at risk of serious infections and severe systemic inflammatory responses that could be fatal, especially if the immune system is compromised due to the treatment (Lier, 2018).

Conclusion

In closing, it is understood that death from cancer is a multivariable and composite event precipitated by an uncontrolled proliferation of cells. Numerous DNA mutations can eventually lead to a cancer that could potentially disrupt and destroy the integrity of surrounding organs and structures. These damages, sometimes irreparable, are the phenomena responsible for the death of a person. Today, it is known that the prolonged exposure of substances that are proven harmful, combined along with genetic and environmental factors, can predispose a person to cancer. It remains urgent that policymakers worldwide consider the scientific findings on the etiology of the different diseases in a population to better promote a good quality of life.

References

Figure 1. This image was released by the National Cancer Institute, an agency part of the National Institutes of Health, with the ID 2446 (image) (next).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018). Uterine cancer incidence and mortality – United States, 1999–2016. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/67/wr/mm6748a1.htm

Dvoretsky, P.M., Richards, K.A., Angel, C., Rabinowitz, L., Beecham, J.B., & Bonfiglio, T.A. (1988). Survival time, causes of death, and tumor/treatment-related morbidity in 100 women with ovarian cancer. Human pathology, 19(11), 1273–1279. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0046-8177(88)80281-8

Estadísticas del cáncer. Comprehensive Cancer Information – NCI – NIH. (2024). https://www.cancer.gov/espanol/cancer/naturaleza/estadisticas#:~:text=La%20tasa%20de%20casos%20nuevos,muertes%20de%202018%20a%202022).

Lier, H., Bernhard, M., & Hossfeld, B. (2018). Hypovolämisch-hämorrhagischer Schock [Hypovolemic and hemorrhagic shock]. Der Anaesthesist, 67(3), 225–244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00101-018-0411-z

Sonoda K. (2016). Molecular biology of gynecological cancer. Oncology letters, 11(1), 16–22.https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2015.3862

Uterine sarcoma treatment. Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University: Feinberg School of Medicine. (n.d.). https://www.cancer.northwestern.edu/types-of-cancer/gynecologic/uterine-sarcoma.html

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Cáncer. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer

Yale Medicine. (2022, February 4). Small cell lung cancer. Yale Medicine. https://www.yalemedicine.org/conditions/small-cell-lung-cancer#:~:text=Due%20to%20how%20quickly%20it,bones%2C%20adrenal%20glands%20and%20brain.

Yue, X., Pruemer, JM, Hincapie, AL, Almalki, ZS, & Guo, JJ (2020). Economic burden and treatment patterns of gynecologic cancers in the United States: evidence from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey 2007-2014. Journal of gynecologic oncology, 31(4), e52. https://doi.org/10.3802/jgo.2020.31.e52