This article was published on Arbona Health Hub Volume 1 Issue 2 (ISSN: 3065-5544).

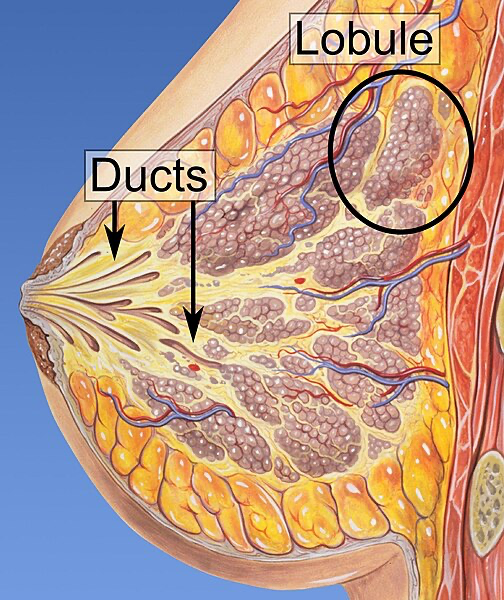

Breast feeding is vital for the nutrition and immune system development of the newborn. To fulfill this function, breast tissue undergoes processes of differentiation or “activation” at the histological level to begin the production of breast milk and develop the necessary structures for its expulsion. Four stages of differentiation of this tissue have been described: Proliferative, in which there is extensive growth in the number and size of epithelial cells during conception and pregnancy; Secretory, characterized by an increase in adipose tissue in the form of large droplets, biochemical changes prior to lactation, and inhibition of milk secretion by progesterone; Secretory Activation, in which progesterone levels drop and prolactin levels rise, allowing for the active secretion of milk along with the expression of milk protein genes; and lactation, which is the continuous production of milk, divided into colostrum stage (high immunoglobulin content) and mature secretion stage (high milk volume for neonatal support), a process dependent on the presence of adipose tissue (Anderson et al., 2007).

It has been observed that this reorganization and proliferation of tissue, followed by apoptosis and immune response at the end of lactation, has the potential to cause pregnancy-associated breast cancer, given that adipose tissue secretes growth factors that can promote tumorigenesis by increasing vasculogenesis and angiogenesis, in addition to serving as a source of energy, fatty acids, and cholesterol (Kothari et al., 2020). Given this information, it is important to determine if the breastfeeding process after childbirth represents a risk factor for developing breast cancer.

Findings

The data found indicated that to explain the association between breastfeeding and breast cancer, it is necessary to involve the parity factor, physical activity, diet and the subtype of breast cancer. The subtypes of this disease can be separated into positive (+) or negative (-) for Estrogen or Progesterone receptor, that is, +ER/-ER or +PR/-PR and the triple negative (-ER/-PR) which is also negative for the type 2 receptor of the human epidermal growth factor (HER2). A study found that breastfeeding is a protective factor against negative hormone receptors (-ER/-PR/-HER2). However, no association was found with the subtypes of hormone receptor-positive (+ER/+PR). Additionally, it was found that breastfeeding for more than 12 months represented a 4% decrease in breast cancer incidence, and parity provided an additional 7% (Islami et al, 2015). Regarding the triple-negative subtype, it was observed that breastfeeding not only served as a protective factor, but the duration is another factor to consider, given that mothers who breastfed for more than 6 months had an 82% reduction in risk (Ma et al, 2017). Although these percentages are different in both studies, both assert that breastfeeding reduces the risk of incidence.

Additionally, another study of 7,663 women in Malaysia found that, along with breastfeeding, consuming soy foods and engaging in physical activity are other protective factors, with breastfeeding being the strongest predictor for breast cancer. It is worth noting that this study also found that consuming alcohol and having a high BMI are risk factors, again highlighting the importance of adipose tissue, both in the breasts and throughout the body, in the cancer development process (Tan et al, 2018).

On the other hand, it was found that just as breastfeeding can affect the incidence of breast cancer, the breastfeeding process can be interrupted in patients who have survived the disease and its treatment. Due to the irradiation or removal of tissue when treating this disease, the burden of breastfeeding may fall on only one breast, causing pain to the mother, a decrease in milk production and duration of breastfeeding, and psychological insecurity about the viability of breastfeeding and the quality of the milk (Ogg et al, 2020; Azim et al, 2010; Gorman et al, 2009). However, studies have confirmed that it is possible to breastfeed if the psychological aspect is addressed through counseling and the help of multidisciplinary teams, given that it has been observed that the doctors handling these patients’ cases have erroneously recommended that they abstain from breastfeeding. This support would provide mothers with the necessary and vital tools to obtain the protective benefits of breastfeeding against the recurrence of cancer (Bhurosy et al, 2021; Azim et al, 2010).

It is worth noting the lack of studies conducted in the field of survivor patients with aspirations to become mothers or pregnant women who wish to breastfeed their children. Most, if not all, of the aforementioned studies highlighted the lack of research on breastfeeding experiences once breast cancer treatments are completed and how this could eliminate their protection. This is why greater attention should be paid not only to treatment during the illness but also after it, to ensure the quality of life for these patients who have already gone through a highly stressful stage in their lives. This would allow for the creation of treatments and preventive measures with a better approach and, in turn, increase the efficiency of those already in place.

Conclusion

It can be observed that the process of breastfeeding and its duration have an inverse relationship with breast cancer for the negative subtypes (-ER/-PR) and triple-negative (-ER/-PR/-HER2), but no significant association was found with the positive subtypes (+ER/+PR). In other words, a longer duration of breastfeeding reduces the risk of the negative subtypes of breast cancer (-ER, -PR and -ER/-PR/-HER2). Parity, physical activity, and the consumption of soy in foods along with breastfeeding are other protective factors against the incidence of this disease. Likewise, this disease can interrupt the breastfeeding process in survivor mothers if they are not treated with counseling and support from multidisciplinary teams during this process. This shows a reciprocal relation in which breastfeeding protects against negative subtype breast cancers, but the disease can also affect or eliminate said protection if it causes the mother to stop breastfeeding. Finally, it is urgent to study the experiences and difficulties that patients who aspire to be or are already mothers may face once they have overcome the disease, in order to determine better treatment and prevention measures to maximize their efficiency.

References

Figure 1. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Lobules_and_ducts_of_the_breast.jpg

Bhurosy, T., Niu, Z., & Heckman, C. J. (2021). Breastfeeding is possible: A Systematic Review on the Feasibility and Challenges of Breastfeeding Among Breast Cancer Survivors of Reproductive Age. Annals of Surgical Oncology, 28(7), 3723-3735. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-020-09094-1

Anderson, S. M., Rudolph, M. C., McManaman, J. L., & Neville, M. C. (2007). Key stages in mammary gland development. Secretory activation in the mammary gland: ¡it’s not just about milk protein synthesis! Breast cancer research: BCR, 9(1), 204. https://doi.org/10.1186/bcr1653

Kothari, C., Diorio, C., & Durocher, F. (2020). The Importance of Breast Adipose Tissue in Breast Cancer International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(16), 5760. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21165760

Islami, F., Liu, Y., Jemal, A., Zhou, J., Weiderpass, E., Colditz, G., Boffetta, P., & Weiss, M. (2015). Breastfeeding and breast cancer risk by receptor status–a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Oncology : official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology, 26(12), 2398-2407. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdv379

Ma, H., Ursin, G., Xu, X., Lee, E., Togawa, K., Duan, L., Lu, Y., Malone, K. E., Marchbanks, P. A., McDonald, J. A., Simon, M. S., Folger, S. G., Sullivan-Halley, J., Deapen, D. M., Press, M. F., & Bernstein, L. (2017). Reproductive factors and the risk of triple-negative breast cancer in white women and African-American women: a pooled analysis. Breast cancer research : BCR, 19(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-016-0799-9

Tan, M. M., Ho, W. K., Yoon, S. Y., Mariapun, S., Hasan, S. N., Lee, D. S., Hassan, T., Lee, S. Y., Phuah, S. Y., Sivanandan, K., Ng, P. P., Rajaram, N., Jaganathan, M., Jamaris, S., Islam, T., Rahmat, K., Fadzli, F., Vijayananthan, A., Rajadurai, P., See, M. H.,… Teo, S. H. (2018). A case-control study of breast cancer risk factors in 7,663 women in Malaysia. PloS One, 13(9), e0203469. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203469.

Ogg, S., Klosky, J. L., Chemaitilly, W., Srivastava, D. K., Wang, M., Carney, G., Ojha, R., Robison, L. L., Cox, C. L., & Hudson, M. M. (2020). Breastfeeding practices among childhood cancer survivors Journal of cancer survivorship : research and practice, 14(4), 586-599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-020-00882-y

Azim, H. A., Jr., Bellettini, G., Liptrott, S. J., Armeni, M. E., Dell’Acqua, V., Torti, F., Di Nubila, B., Galimberti, V., & Peccatori, F. (2010). Breastfeeding in breast cancer survivors: pattern, behaviour and effect on breast cancer outcome Breast (Edinburgh, Scotland), 19(6), 527-531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.breast.2010.05.018

Gorman, J. R., Usita, P. M., Madlensky, L., & Pierce, J. P. (2009). A qualitative investigation of breast cancer survivors’ experiences with breastfeeding. Journal of cancer survivorship : research and practice, 3(3), 181-191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-009-0089-y