Introduction

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is an important tool for understanding the structure and function of the brain. This non-invasive imaging technique is excellent at showing small anatomical details, allowing scientists and medical professionals to explore the anatomy of the brain’s tissues and structures. Strong magnets and radio waves are used in an MRI to produce detailed images, in contrast to conventional imaging methods like computed tomography (CT) scans, which use X-rays, and Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scans, which use radioactive tracers. This is especially useful in neuroimaging as it not only removes the dangers related to ionizing radiation but also provides better soft tissue contrast.

Functional MRI (fMRI) is a powerful tool that has revolutionized our understanding of the brain’s function. By measuring changes in blood flow associated with neural activity, fMRI enables the mapping of brain regions involved in specific tasks or cognitive processes. This imaging technique offers several advantages over other methods such as CT scans and PET scans. However, it also has its limitations that need to be considered when evaluating its utility in brain imaging.

Although the use of MRI has advanced our understanding of the brain, it’s important to recognize its advantages and disadvantages. MRI is excellent at displaying soft tissues, which makes it perfect for in-depth investigations of the brain. It provides multiplanar imaging and high spatial resolution, enabling a comprehensive look of the brain from multiple perspectives. MRI does have several drawbacks, too, such as its propensity to be affected by noise from motion, lengthier acquisition periods, and difficulties imaging specific structures. Despite these issues, MRI’s advantages have driven the technology to the front lines of neuroscience, greatly advancing both clinical and research efforts related to the diagnosis of brain disorders.

MRIs

MRIs contribute to our understanding of the brain’s structure and function through its ability to generate high-resolution images with excellent soft tissue contrast. It allows for the visualization of different brain regions, including grey matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid, facilitating the identification of anatomical abnormalities, lesions, and changes in brain morphology. Moreover, fMRI techniques enable the assessment of brain activity and connectivity, providing insights into cognitive processes and neural networks.

When it comes to brain imaging, MRI uses a variety of sequences, each with an individual purpose. Frequently used sequences include T1, which provides a broad definition of anatomy and tissue characterization; T2, which displays pathology and edema as a high or “white” signal; fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR), which decreases the amount of cerebrospinal fluid signal and makes “white” pathology simpler to observe; gradient echo imaging, or susceptibility imaging, which is sensitive to broken blood products; and diffusion-weighted imaging, which is essential for acute stroke diagnosis as it shows altered water motion. The use of post-contrast imaging, usually T1-weighted with fat suppression, becomes essential for examining the blood-brain barrier’s integrity.

MRI boasts several advantages in neuroimaging, making it a preferred modality for assessing brain structure and function. Its superior soft tissue contrast provides high-resolution images, allowing for the differentiation of various brain structures, including gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid. The ability to conduct multi-planar imaging without repositioning the patient is a notable advantage, offering comprehensive views of the brain from different angles. fMRI introduces a functional dimension, measuring changes in blood flow to assess brain activity and connectivity. Importantly, MRI’s absence of ionizing radiation makes it a safer choice for repeated imaging, especially in pediatric and longitudinal studies.

However, MRI also comes with its set of limitations. The cost and accessibility of MRI equipment and procedures can be prohibitive, restricting access in certain healthcare settings and geographic regions. Patient cooperation is crucial, as MRI requires individuals to remain still for an extended period, presenting challenges for those with claustrophobia, agitation, or specific medical conditions. Sensitivity to motion artifacts is another limitation, as movement during scanning can lead to image distortions. Additionally, the compatibility of MRI with certain metallic implants or devices poses safety concerns due to the strong magnetic field, limiting its use in individuals with such implants.

fMRI

fMRI contributes to our understanding of the brain’s function by providing real-time information about neural activity associated with specific tasks or cognitive processes. This imaging technique has been used to investigate a wide range of cognitive and affective processes, including attention, memory, emotion, and decision-making. fMRI has also been used to study brain disorders such as schizophrenia, depression, and anxiety, providing valuable insights into the neural mechanisms underlying these conditions.

However, fMRI has limitations, including higher cost and complexity of equipment, susceptibility to motion artifacts, and limitations related to its temporal resolution. Additionally, fMRI measures changes in blood flow associated with neural activity, which is an indirect measure of neural activity and may be influenced by factors such as vascular physiology and neurovascular coupling.

CT and PET

CT scans can be helpful to diagnose acute cerebral diseases like bleeding or fractures because they provide quick imaging with great spatial resolution. In contrast to MRI, CT produces less soft tissue contrast while requiring ionizing radiation.

PET scans provide functional information by visualizing metabolic and molecular processes in the brain by radiotracers. However, PET is not commonly used for regular anatomical imaging due to its inferior spatial resolution and need for ionizing radiation exposure.

PET/MRI

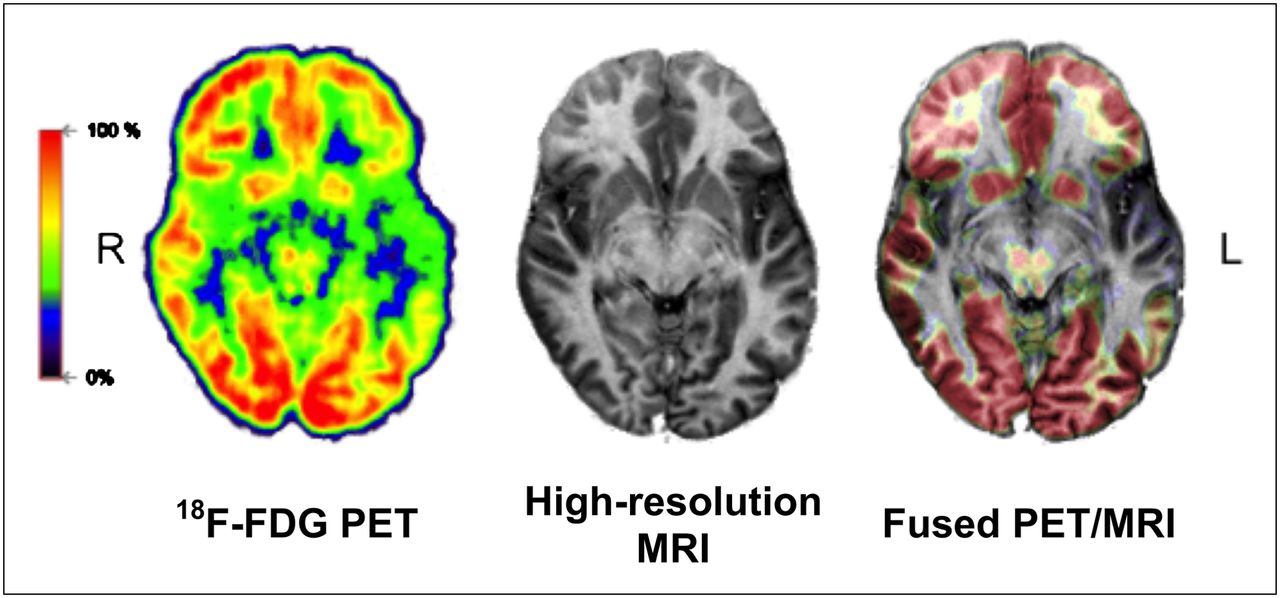

The integration of PET with MRI has revolutionized our understanding of the brain’s structure and function. This hybrid imaging modality, PET/MRI, offers a unique combination of molecular, functional, and anatomical information, providing unprecedented insights into neurobiology and neurological disorders. Understanding the contributions, advantages, and limitations of PET/MRI in neuroimaging is essential for comprehending its impact on brain research and clinical practice.

PET/MRI contributes to our understanding of the brain’s structure and function through its ability to simultaneously acquire molecular and functional data alongside high-resolution anatomical images. The combination of PET and MRI modalities in PET/MRI enables comprehensive assessments of neurobiology, including the detection of neurodegenerative processes, characterization of brain tumors, and evaluation of neurovascular function.

Advantages of PET/MRI include its ability to provide multi-parametric imaging, offering a holistic view of brain structure, function, and molecular processes in a single examination. Additionally, PET/MRI does not involve ionizing radiation, making it safer for longitudinal studies and suitable for pediatric and research applications. The superior soft tissue contrast of MRI enhances the localization and characterization of molecular PET findings within the brain. However, PET/MRI also presents challenges, including the complexity of data fusion, longer acquisition times, and the need for specialized expertise in interpreting multi-modal imaging datasets.

In comparison to standalone PET or MRI, PET/MRI offers a synergistic approach that leverages the strengths of both modalities, providing a more comprehensive understanding of brain structure and function. While PET provides molecular insights, MRI contributes detailed anatomical and functional information, creating a powerful tool for unraveling the complexities of the brain.

Conclusion

MRI contributes significantly to our understanding of the brain’s structure and function, providing detailed anatomical and functional insights with superior soft tissue contrast. Its non-ionizing nature enhances safety, making it ideal for repeated imaging, especially in vulnerable populations. While functional imaging capabilities, like fMRI, offer dynamic insights into brain activity, MRI has limitations, including cost barriers and challenges related to patient cooperation. The synergy with CT scans and PET scans is evident, each offering unique advantages, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive approach in neuroimaging. PET/MRI represents a paradigm shift, providing a holistic view of neurobiology with multi-parametric imaging and safety benefits, positioning it as a valuable tool for research and clinical applications.

References

- Caria, A.; Sitaram, R.; Birbaumer, N. (2012). Real-Time fMRI: A Tool for Local Brain Regulation. The Neuroscientist, 18(5), 487–501. doi:10.1177/1073858411407205

- Deck, Michael D.F.; Henschke, Claudia; Lee, Benjamin C.P.; Zimmerman, Robert D.; Hyman, Roger A.; Edwards, Jon; Saint Louis, Leslie A.; Cahill, Patrick T.; Stein, Harry; Whalen, Joseph P. (1989). Computed tomography versus magnetic resonance imaging of the brain a collaborative interinstitutional study. Clinical Imaging, 13(1), 2–15. doi:10.1016/0899-7071(89)90120-4

- Helms, Gunther (2016). Segmentation of human brain using structural MRI. Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology and Medicine, 29(2), 111–124. doi:10.1007/s10334-015-0518-z

- Jadvar H, Colletti PM. Competitive advantage of PET/MRI. Eur J Radiol. 2014 Jan;83(1):84-94. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.05.028. Epub 2013 Jun 18. PMID: 23791129; PMCID: PMC3800216.

- Mirzaei G, Adeli H. Segmentation and clustering in brain MRI imaging. Rev Neurosci. 2018 Dec 19;30(1):31-44. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2018-0050. PMID: 30265656.

Image credits

In order of appearance:

- Atia N, Benzaoui A, Jacques S, Hamiane M, Kourd KE, Bouakaz A, Ouahabi A. Particle Swarm Optimization and Two-Way Fixed-Effects Analysis of Variance for Efficient Brain Tumor Segmentation. Cancers. 2022; 14(18):4399. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14184399

- https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Figure_8.fMRI_image_showing_activity_in_the_default_mode_network_during_hypnosis_%28Graner_et_al.,%282013%29.png

- https://www.kcl.ac.uk/news/new-database-of-healthy-adult-human-brain-pet-mri-and-ct-images-is-now-available-for-research

- Ciprian Catana, Alexander Drzezga, Wolf-Dieter Heiss, Bruce R. Rosen; PET/MRI for Neurologic Applications; Journal of Nuclear Medicine Dec 2012, 53 (12) 1916-1925; DOI: 10.2967/jnumed.112.105346