Introduction

The vaginal microbiome is a complex microbial community that inhabits the female genital tract and exists in a symbiotic relationship with the host, the host being the human. The host provides oxygen, glucose, and nutrients, while certain microbe profiles are thought to promote vaginal health or can be a sign of infection or disease.

The Vaginal Microbiome

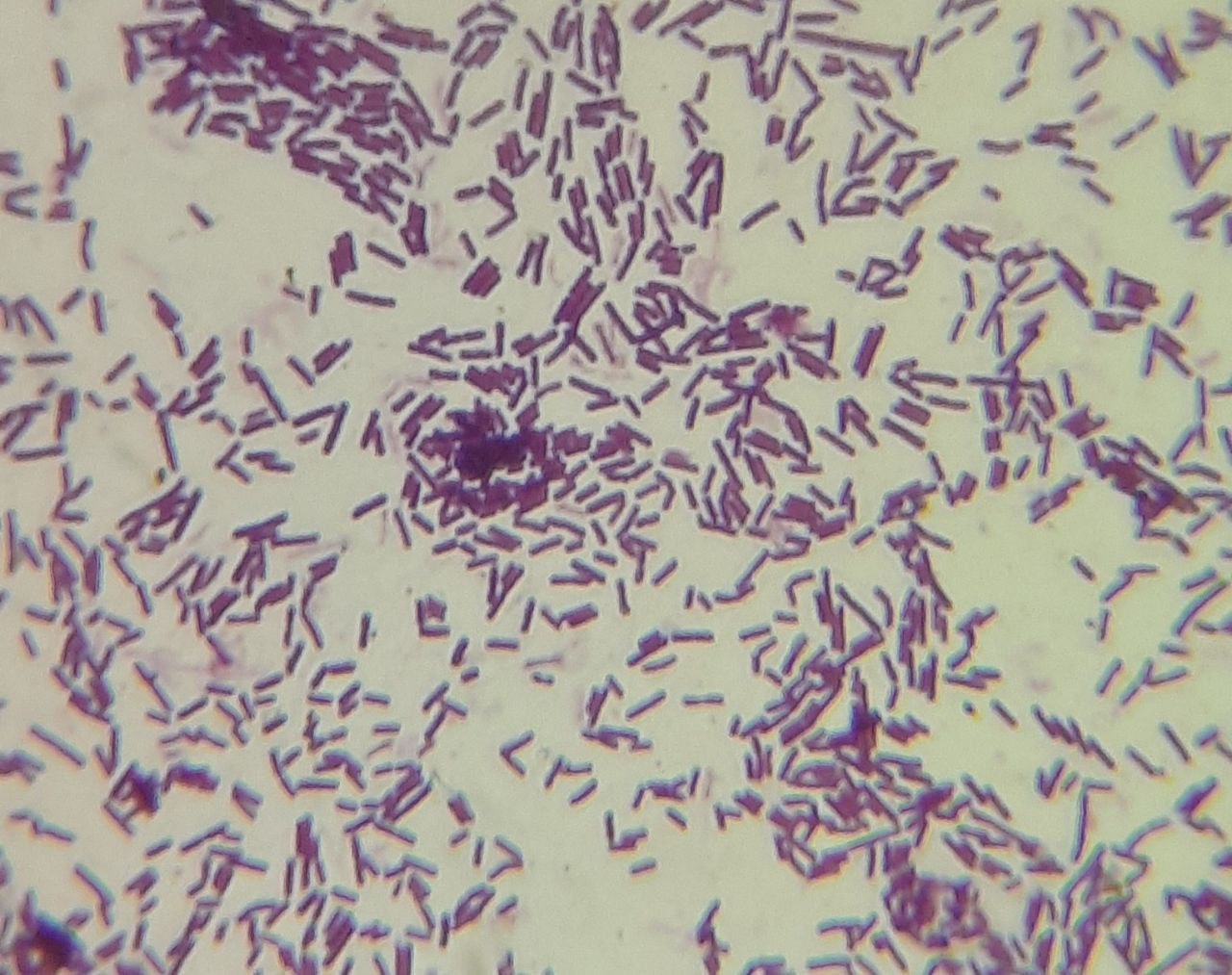

The Lactobacillus genus is thought to be the major component of the vaginal microbiome in healthy women of reproductive age by producing lactic acid as a fermentation product that lowers the vaginal pH to approximately 3.5-4.5. Usually, Lactobacillus species, L. iners, L. crispatus, L. gasseri, and L. jensenii have been shown to predominate in varied proportions. Genomic analyses have provided evidence that each possesses a unique range of protein families and suggest these differences may reflect specific community adaptations. Other genus such as Gardnerella, has been associated with a higher risk of bacterial vaginosis (BV) and preterm birth.

Collection and Sequencing

Collection of the vaginal microbiome is most commonly through vaginal swabs, these being self-collected or collected with the help of a physician. Depending on the kit used, after collection, it may need to be stored in the freezer while some may not require it. Swabs must be inserted a few inches into the vagina and gently moved in a circular motion along the walls of the vagina for 10-30 seconds. After this, the swab should be carefully removed without touching the folds of the skin outside the vagina and placed into the tube.

After bacterial DNA or RNA extraction of the sample is done, sequencing of the microbiome takes place. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is a modern technology used for determining the sequence of DNA or RNA to study genetic variation associated with diseases or other biological factors. The most common NGS technique used in vaginal microbiome studies is 16S Ribosomal RNA Sequencing. 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing can only identify bacteria and archaea because it targets and reads a region of the 16S rRNA gene that is present in these microorganisms.

Vaginal Health Factors

When it comes to discussing a “healthy” vaginal microbiome, it’s important to recognize that this concept can vary significantly from one individual to another. The composition of the vaginal microbiome is influenced by a multitude of internal and external factors. Therefore, what constitutes a “healthy” vaginal microbiome for one person may differ from what is considered optimal for another. It’s this intricate interplay of diverse factors that shapes the unique microbial environment of the vagina for each individual.

Internal factors:

- Ethnicity

- Reproductive hormone levels

- Immune System

- Life stage (infant, puberty, pregnancy or menopause)

External factors:

- Contraceptive use

- Diet

- Exercise

- Antibiotics/antifungals

- Infections

- Sexual activity

A study showed that hispanic and black women tend to show higher median pH values that reflect a higher prevalence of communities not dominated by Lactobacillus species compared to Asian and white women. Another study showed that participants not using hormonal contraceptives and those using combined contraceptives showed similar periodic fluctuations of vaginal microbiota that correspond to stages of the menstrual cycle and high average Lactobacillus abundances. While participants using progestin-only contraceptives had altered periodic fluctuations of the vaginal microbiota and low average abundances of Lactobacillus.

Given these findings, a healthy vaginal microbiota could be described as a microbial community that provides a function that is sufficiently advantageous to the host and is not limited by its composition. Several types of vaginal communities could fulfill this function. Different vaginal microbiota types, with or without lactobacilli, may be deemed “healthy” in this context if they show no symptoms and have varying degrees of susceptibility to infections.

Importance

In addition to helping to better define health and advance disease diagnostics, a deeper understanding of normal and healthy vaginal ecosystems based on their actual functions rather than just their composition would enable the development of more individualized regimens to promote health and treat illnesses. This deeper understanding could lead to the identification of specific microbial communities and their interactions within the vaginal environment, shedding light on how these communities contribute to overall health or predispose individuals to certain illnesses. By focusing on the functionality of these ecosystems, researchers and healthcare providers can work towards personalized interventions that target the root causes of imbalances, rather than employing broad-spectrum approaches that may not address the specific needs of each individual. Furthermore, the development of individualized regimens could lead to more effective treatment strategies, potentially reducing the prevalence of certain vaginal infections and related health issues.

Future directions

- Assess the relationship between the vaginal microbiome composition and the phases of the menstrual cycle, and determine if at any given phase one could be more prone to infection due to microbiome composition.

- Explore the role of human genetics and physiology in health and diseases on the vaginal microbiome.

References

- Ravel J, Gajer P, Abdo Z, Schneider GM, Koenig SS, McCulle SL, Karlebach S, Gorle R, Russell J, Tacket CO, Brotman RM, Davis CC, Ault K, Peralta L, Forney LJ. Vaginal microbiome of reproductive-age women. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 Mar 15;108 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):4680-7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002611107. Epub 2010 Jun 3. PMID: 20534435; PMCID: PMC3063603.

- Song SD, Acharya KD, Zhu JE, Deveney CM, Walther-Antonio MRS, Tetel MJ, Chia N. Daily Vaginal Microbiota Fluctuations Associated with Natural Hormonal Cycle, Contraceptives, Diet, and Exercise. mSphere. 2020 Jul 8;5(4):e00593-20. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00593-20. PMID: 32641429; PMCID: PMC7343982.

- Lewis FMT, Bernstein KT, Aral SO. Vaginal Microbiome and Its Relationship to Behavior, Sexual Health, and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Apr;129(4):643-654. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001932. PMID: 28277350; PMCID: PMC6743080.

- Verstraelen H, Vieira-Baptista P, De Seta F, Ventolini G, Lonnee-Hoffmann R, Lev-Sagie A. The Vaginal Microbiome: I. Research Development, Lexicon, Defining “Normal” and the Dynamics Throughout Women’s Lives. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2022 Jan 1;26(1):73-78. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000643. PMID: 34928256; PMCID: PMC8719517.

- Chen X, Lu Y, Chen T, Li R. The Female Vaginal Microbiome in Health and Bacterial Vaginosis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021 Apr 7;11:631972. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.631972. PMID: 33898328; PMCID: PMC8058480.

- Hočevar, K., Maver, A., Vidmar Šimic, M., Hodžić, A., Haslberger, A., Premru Seršen, T., & Peterlin, B. (2019, August 27). Vaginal microbiome signature is associated with spontaneous preterm delivery. Frontiers. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2019.00201/full

- https://blog.microbiomeinsights.com/16s-rrna-sequencing-vs-shotgun-metagenomic-sequencing#:~:text=Unlike%2016S%20rRNA%20sequencing%2C%20shotgun,microorganisms%20at%20the%20same%20time.

- Ruairi Robertson, P. (2023b, September 11). 16S rrna gene sequencing vs. shotgun metagenomic sequencing. 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing vs. Shotgun Metagenomic Sequencing. https://blog.microbiomeinsights.com/16s-rrna-sequencing-vs-shotgun-metagenomic-sequencing#:~:text=Unlike%2016S%20rRNA%20sequencing%2C%20shotgun,microorganisms%20at%20the%20same%20time.